I often hear from patients so frustrated in their search for a diagnosis, they no longer care what it’s called. “I’m so tired looking for answers.” “I just want to feel better.” “Why can’t someone help me?”

Too often, they’re experiencing a level of intractable pain and exhaustion that leaves them living a subterranean existence, no longer able to work or leave their beds. I know from my own experience that this kind of pain-with-no-name disrupts sleep, work, time with family, clear-headed thinking, planning, and evaluation. All of which makes the process harder.

More American adults are misdiagnosed every year than are diagnosed with heart disease, cancer and stroke together!

Why is Getting an Accurate Diagnosis So Important? My son nearly died at 15 because he was misdiagnosed over 15 times. His treatments temporarily camouflaged his progressing symptoms. When the treatments became ineffective, and his doctors refused to reconsider his diagnosis, we nearly lost him. Curing the source of illness is better than just treating the symptoms. It might be scary to read this but without an accurate root cause, you will not get better.

That’s why we all need a correct diagnosis, one that will lead to effective treatment. Nothing much happens in healthcare without it. But if your diagnosis is missing or wrong, little else your doctor does can ever fully work except to camouflage your initial symptoms. Why that’s true and how it works is important to understand.

What is a Diagnosis?

It’s a medical explanation of what is happening in your body that is causing new or progressing symptoms. Plus it’s the linchpin for the medicines you take, the treatments you get, and the surgeries you may have. Too often you’re sent home with an official list of symptoms but that doesn’t equal a diagnosis. There are almost 23 thousand medical conditions but only a few hundred symptoms.

Think of it as a scientific version of the Mad Libs game where you fill in the blanks with nouns, verbs and adjectives. You’re looking for the most precise answer, though, not the silliest.

Here's an example: Your heart isn’t beating effectively (symptom) because your arteries are clogged blocking blood flow (cause). Then you need to learn why that’s happening. The why is the diagnosis. When arteries leading to the heart are narrowed, it’s called coronary artery disease (CAD). It happens due to a buildup of fatty deposits. Why are fatty deposits lining the arteries? There are many possible reasons including chronic high blood pressure, high cholesterol and the effects of smoking. Finding the right reason usually means you can treat or cure the symptoms.

What if my diagnosis is wrong?

There are three requirements for a good diagnosis; it should be accurate, communicated, and timely. Accurate means it’s the correct explanation for your symptoms. Communicated means someone has spoken to you to explain the diagnosis and answered your questions. Timely is less precise. It’s dependent on standards of care and how complex the medical condition is or if the symptoms are identifiable. For example, if you break your leg skiing, you’ll know it quickly. If you have sepsis, it might take a day or two to confirm. If you’re having a stroke, time is of the essence. There’s an ER saying when a stroke happens, “Time is brain.”

If any of those three criteria are missing, you’ve been misdiagnosed.

Getting the right diagnosis is a team effort…your goals and needs should be at the center of that effort.

More American adults are misdiagnosed every year than are diagnosed with heart disease, cancer and stroke together! That includes being told the wrong diagnosis, dismissed, gaslighted, told you’re fine when you’re not, never hearing from the doctor, and learning of your diagnosis late. One medical condition that’s routinely missed for 10 years is endometriosis. That’s not acceptable even if it’s common.

People with rare diseases experience this the most. It can take years to learn if your medical condition is considered rare. Yet, there are so many rare diseases that when you add them up, one in ten Americans has a rare disease. (We’ll cover how to deal with being dismissed by your doctors and what you need to know about rare diseases thoroughly in future chapters.)

How Should Getting a Diagnosis Work?

The diagnostic process is complex, because it involves many people and moving parts. You have the most important role in getting properly diagnosed because you’re the only one who truly has skin in the game. Everyone else there is paid to support you.

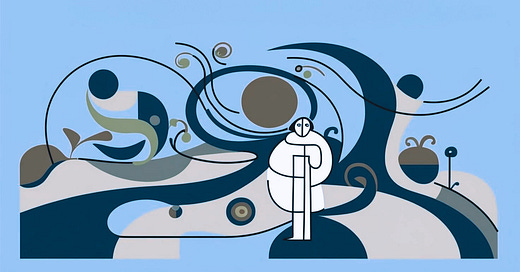

This is a diagnostic process map. It details the steps between you asking for help and getting the answers and help you need.

It starts with you. You’re not feeling well so you make an appointment to see your primary care doctor or you’re feeling dangerously ill so you go to an emergency room. Your diagnosis is not something doctors can magically guess on their own when you walk into the exam room. It’s a multi-step process that starts when you arrive, armed with information only you can share. Communicating what you’re experiencing and how it differs from what you usually feel like is just step one. [See Chapter 2 for how to record your history in advance.]

The doctor’s first steps should be to review your medical history, including your family’s medical history, and your current symptoms, followed by a physical exam. Maybe your blood and urine will be tested or they’ll order an x-ray. They may add more targeted tests depending on your symptoms. The tests for a headache will be different from those for chest pain or stomach issues or fever or backache.

The results of your history, physical exam, and any tests can be clues to identifying the cause of your symptoms. The answers could be simple –– you broke your leg –– or extremely complex and difficult to figure out –– you’re experiencing a rare chronic disease.

Getting the right diagnosis is a team effort. Because you’re the only one who really knows yourself, your goals and needs should be at the center of that effort. Everyone else ––the doctors or specialists, the nurses, the assistants, the lab technicians and other professionals –– are focused on identifying what is causing your symptoms.Then, your doctors share their conclusions and a plan for treatment is discussed. You can ask questions and make an informed decision about the treatment. This is what is known as a Working Diagnosis. It’s a step in the process but isn’t necessarily the end of it. (See Step 4.) Trying a treatment is is just the next step. If the treatment is expensive or invasive like surgery, it requires more conversation and I highly recommend a second opinion. (We’ll discuss that in Chapters 11 and 14.)

No News is No News. If no one tells you the diagnosis, than you haven’t been accurately diagnosed. Unfortunately, the responsibility for follow up is on the patient’s shoulders. (How and when to do that will be covered in Chapters 10, 11 and 12.)Look at the map again. That red line shows the feedback loop after a diagnosis is communicated to you and a treatment is tried. If the treatment doesn’t solve the problem, your medical team should suggest alternatives. Precision medicine can be very helpful in choosing the right treatment but many doctors are hesitant to order it since too often insurance companies won’t pay for the genetic tests needed.

If your new treatment still isn’t helping, the diagnosis needs to be reevaluated. The team should return to the big wheel for more information gathering like more tests or deeper, more detailed questions. That’s normal and it’s how the diagnostic process is supposed to work. But nothing happens unless you report that the treatment isn’t working or you feel worse. The No News is No News paradigm works both ways.

If your doctors aren’t willing to give your symptoms a fresh look, that’s a cognitive bias and you need an independent second opinion. (Chapter 11 will be dedicated to second opinions.)

What Control Do You Have in the Diagnostic Process?

The best approach to medical teamwork is shared decision making. That means you share your goals and preferences and the doctors tell you about your options, discuss them in detail and work with you to make informed choices. That’s a good measure of control.

As covered in Chapter 2, you also control ensuring they have all of your relevant medical history. In fact, the sole purpose of this book is to put you in the driver’s seat of your own healthcare. We’ll cover preparing for an emergency, a primary care visit, for tests, for surgery and much more. Revisit the list of upcoming chapters any time.

What you don’t control is the quality of care where you live, your insurance policy’s willingness to pay for needed tests and treatments, or your own energy when you’re ill. For the last item, turn to close family members or friends, even volunteers where you worship, who will take you to see the doctor, take notes when you’re with the doctor, and help you research your options.

Please share this with family and friends so they can understand what a diagnosis is, how it works, and advocate for themselves.

Next up: Chapter 4: How To Prepare For An Emergency Now. Just a few steps can help you maintain some control.

© Helene M. Epstein, 2025

Great insights and a path to not just feeling better, but actually being better!

I had no idea that misdiagnoses outnumbered actual diagnoses for such common killers. This is very frightening, but incredibly necessary. Thanks, Helene!